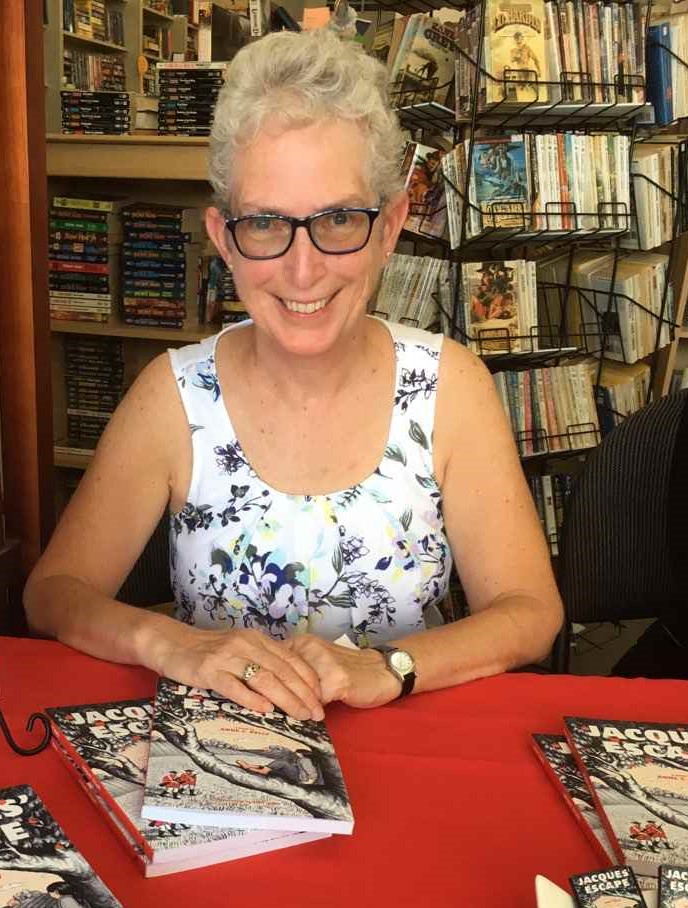

Author spotlight: Anne C. Kelly

Anne Kelly’s first published novel is Jacques’ Escape, released by Trap Door Books in 2019. But she has been reading and writing for as long as she can remember. She got her first taste of sharing her writing in Grade 4, when she wrote a class newspaper with a friend. Anne is an avid reader, and especially enjoys reading historical fiction, crime novels and stories from Atlantic Canada.

As well as being a writer, Anne is an English teacher at heart. She taught English-as-an-Additional-Language (EAL) to adult newcomers to Canada for more than 20 years, and loves learning about different cultures and traditions. She currently works as a English Language Coordinator at the Bedford Public Library. When not reading, writing or working, you’ll find Anne walking, doing yoga, playing piano, or singing with her community choir.

In this Author Spotlight, Anne talks about her first book, which was originally submitted to the Atlantic Writing Competition (now Nova Writes), theWriters’ Fed of Nova Scotia’s competition for unpublished manuscripts, and getting published.

Congratulations! It’s exciting to see that your debut book Jacques’ Escape was shortlisted for the Hackamatack Children’s Choice Award (See the Hackmatack Shortlist 2020-21 here.) What was your reaction when you heard that news?

The nomination came out of the blue for me, so I was surprised. That’s one of the things about having a published book that I didn’t anticipate—that it would take on a life of its own! Jacques’ Escape is being read, discussed, reviewed and nominated for awards without my knowledge—like a child who has headed off to school and a life away from his parents! I am of course thrilled to be nominated, especially since it means so many more children will be encouraged to read it!

Tell me about the book. What’s it about?

Jacques’ Escape is the story of a 14-year-old Acadian boy from Grand Pre. During the Expulsion, Jacques and his family are deported to the British colony of Massachusetts. Jacques longs to escape and join his older brother in fighting with the French. Through his experiences, Jacques comes to know the true meaning of family and home, as well as what it means to be Acadian.

As a first-time author, what was the experience like to get your book published?

Amazing! As I said at my book launch, when I hold a copy of Jacques’ Escape, I’m holding a dream in my hand!

The process of writing this book and having it published was a long and slow one, with multiple rewrites and many rejections. I often felt frustrated and wanted to give up on the whole project. But I loved my characters and believed the story was worth telling. So, I kept rewriting and sending it out again and again.

My publishers at Trap Door Books are wonderful—always supportive and respectful of my story. They truly helped my dream to come true.

I understand that you originally submitted the manuscript for Jacques’ Escape to the Writers’ Fed’s Atlantic Writing Competition (now called Nova Writes) and that you won the category you submitted in, back in 2001. Why is this program important to writers such as yourself?

I find that I lose the ability to look at my writing objectively, especially once I’ve begun the editing and rewriting stage. Programs such as Nova Writes give developing authors clear, written feedback, practical suggestions, and lots of encouragement!

The book is fictional, but obviously grounded in fact. Why did you decide to take this approach?

I personally love historical fiction. It brings history alive for me. I was never as interested in facts and dates as I was in the what life was like in the past—what did people eat and wear? Why did they do what they did? How did they feel about what was happening around them? I first learned about the Deportation of the Acadians when I was in Grade four, and for many years I wondered what life was like for the families once they were driven out of Acadia. What happened? Where did they go? How did they feel? So, I set out to answer those questions.

How did you do the research for your book? What was involved?

I started out by reading everything I could get my hands on about the Acadians, and I read until the books all began to say the same things! I took many, many notes, which I referred to as I wrote. I visited Grand Pre and some of the other Acadian sites in Nova Scotia, then went to Boston to access the Massachusetts Archives. That was really exciting for me—holding and reading original documents that dated back to the 1700’s.

Much of my research was done before the internet became so fast and easy to use. Although the internet may make some of the material easier to find and access, I don’t think it would change my style very much. Holding books in my hand and being where the events took place gives me a sense of the history in a more powerful way than reading an online article ever could.

Your book is quite beautiful to hold, with illustrations by Helah Cooper. Did you work with the illustrator? What was the process like?

I didn’t actually see the illustrations until they were almost finished, when they were sent to me to preview. And I didn’t meet Helah until the book launch. But I was amazed at how she took my words and turned them into pictures!

Like everyone else at Trap Door Books, Helah was respectful of my story and my opinion. There was one illustration that I felt wasn’t dramatic enough for the scene it was portraying. I hesitated before expressing my opinion, but Helah willingly made the changes for me.

I love the way the book looks, the cover, the pictures, the blue and red text. As one of my daughters commented, it looks like a real book!

When you were a young reader, what books did you love? Was there a book that made you say to yourself, “I’m going to be a writer one day too”?

My two favourite books as a child were Anne of Green Gables by Lucy Maud Montgomery and A Little Princess by Frances Hodgson Burnett. The main characters in both these books—Anne and Sara—are storytellers. I don’t think that’s a coincidence! I don’t remember consciously deciding that I wanted to be a writer. I’ve just loved books and stories—reading and writing them—well, forever!

What are you working on these days? Will you be revisiting the time period?

The novel I am working on now is vastly different from Jacques’ Escape. It is for a slightly older age group and is a mystery of sorts, set in modern day. I don’t have any plans at this time to revisit the Acadians, although many people have asked me whether I am going to write a sequel, so I suppose the possibility is there.

– Questions by Marilyn Smulders

Author spotlight: Anne C. Kelly Read More »