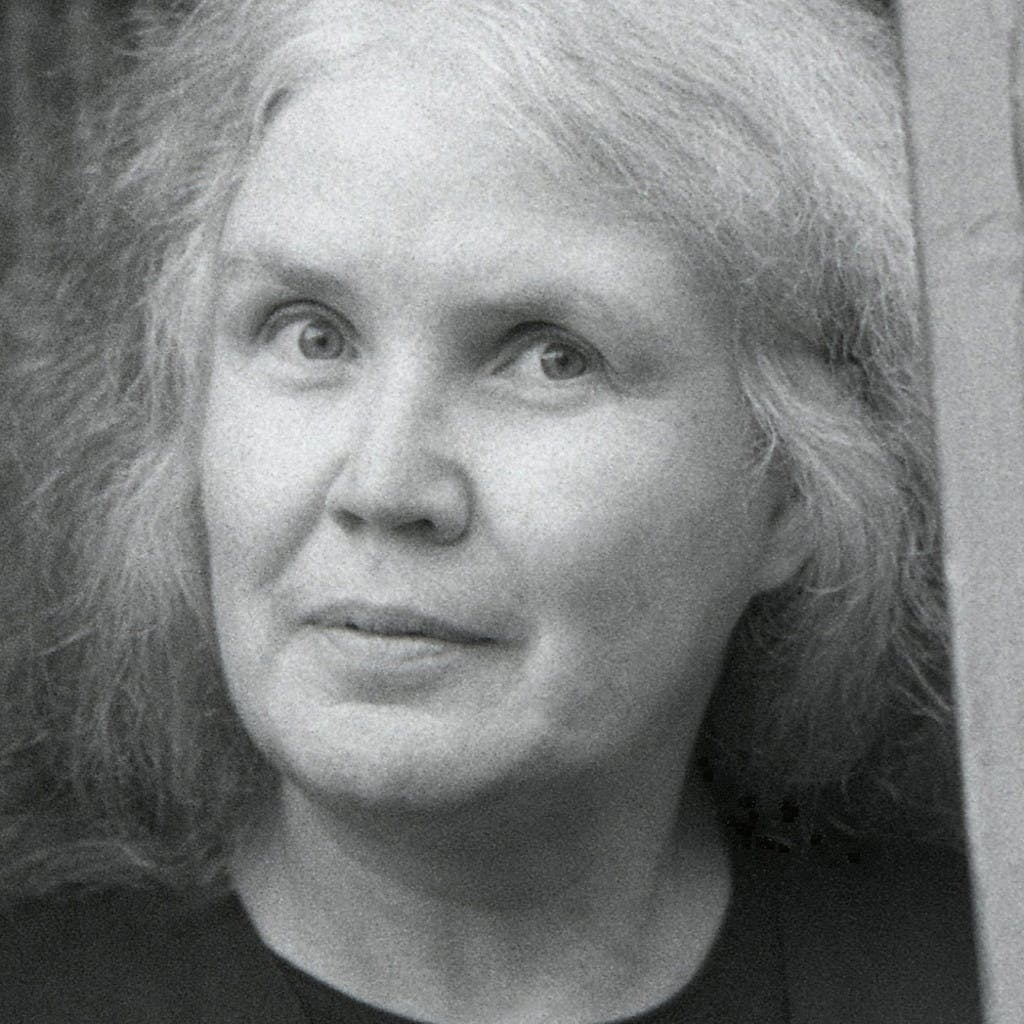

Author spotlight: Janet Barkhouse

Janet Barkhouse is a member of the Writers’ Federation of Nova Scotia, a fiction writer, a children’s writer, and a poet. In the following post, she discusses her influences, how she got started as a writer, and all the things she loves about living in Nova Scotia. Barkhouse’s debut full-length poetry collection,Salt Fires, will be published by Pottersfield Press this fall.

How long have you been writing? What drew you to writing in general, and poetry, fiction, and children’s literature in particular?

I’ve been writing since childhood, largely because of my writer mother’s modeling, or perhaps even the way my genes were shaped; Noah Webster was my mother’s ancestor. I published poems in Loyola College’s journal Amphora when I was going to school in Montréal—had written poems all through my adolescence, as many of us do. One of my professors, smiling, said to me, “Janet, an image is not a poem, you know,” and I thought, “I guess I’m not very good at this—I better stick to acting.” So I “went into” theatre, and acted for years. Still I wrote—plays for my elementary-school-age children, published a poem here, a story there. When I shifted gears and became an educator, I wrote curriculum, essays, a play for students in Drama Club. After I retired, Carole Glasser Langille, whom I’d invited to my classes, phoned me to ask if I’d like to take a poetry workshop she was offering near my home. That was in 2006, and I was smitten. I’ve worked hard to learn how to share ineffable experience in words, and I’m still learning. It has seemed natural to write for children, too, when asked; I remember my own childhood vividly, then had children, then taught adolescents. The stories I’ve had published (Room, CBC) were like poems, riffs on experience. And it’s poems I feel most compelled to write, unless I have a deadline for something. Poems are their own deadline.

What do you think is changing in poetry these days?

Poetry is always the same in its rootstock; the branches grafted on that stock change according to the era and its paradigms. My formal education was almost entirely based in the work of British Isles men. My English Master’s thesis (the word “Master” says it all, doesn’t it?) was called “The Developing Sense of History in the Two Cleopatra’s of Samuel Daniel.” My favourite poets were Elizabethan, Metaphysical, Romantic. The world view of those poets’ times was hierarchical, with God and His Angels at the helm. His Plan and His Reasons lent order to the chaos of daily life. More and more, that world view is being reshaped into that of Existentialism, where life has value, but no meaning, as in Camus’ L’Étranger. In fact, even the sense of life’s intrinsic value is being eroded. We live in interesting times! Poetry has always been the canary in the coal mine; poets are by nature sensitive to climate change, so to speak. Poems today reflect the chaos we seem to be approaching, and the old order of rhythm, rhyme, stanza, meaning, has shifted to reflect a world with no overview, no unbreakable rules, and only subjective meaning. My own poems befit my place in society, showing my background of meaning and structure, but reaching out to touch the face of chaos. “Accessible,” critics would call it.

What do you love about living in Nova Scotia?

What don’t I love about living in Nova Scotia! I love the land. Perhaps this is because I spent my sixth through ninth years playing in the wilds near the Dingle Tower in Jollimore—skating on the Frog Pond, climbing Mount Misery, dabbling in the brook across the road from our flat, exploring the caves formed by huge boulders in John W. MacLeod’s schoolyard, playing on the beach of the Northwest Arm (among other things, watching straight pipes from the millionaires’ homes on the hill disgorge their sewage onto the rocky shore). Now I gather edible mushrooms in the woods behind my home, collect sap from sugar maples for syrup, walk on paths, roads, beaches that offer delightful feasts for the senses. And the people here—family members I’ve played with and loved from a very young age, as well as extended family—neighbours, poets, musicians, artists. Sue Goyette wrote a poem saying music fills our aquifers, “a large rich supply.” That seems exactly right to me, music being both itself and a metaphor for what sings in us all, the light we seek and hope to nurture. My neighbours are people who live close to the land, rural folk, who deal with challenges in the now, whine rarely if ever, grieve deeply and then let sorrow go. Ordinary Nova Scotia folk, not ordinary at all. Community.

What’s the biggest misconception about being a writer?

The biggest misconception about being a writer is that we’re special, which maybe means smarter (?) than the average bear. I’ve been an actor, a teacher, a writer, and I can tell you I’m still the same person I was in each job, a muddled, struggling, mixed bag with occasional moments where all the efforts mesh and allow something to work, speak, through me. We’re no different from any other humans who care about what they do. Of course the stories and poems and TV shows and plays we create are pretty special because, well, imagine how sad we all would be without them, just as we would be without music or art—or the talents that athletes or plumbers or electronics engineers or waiters or any of the people who don’t write but care about their work, share with us.

What advice do you have for aspiring writers?

To aspiring writers I would say, “Believe.” Believe that you can write, and keep on. If you couldn’t write, you wouldn’t want to. You’d want to do something else just as valuable. Something in you is asking to speak through you, and all you have to do is believe that Something has chosen the right writer. When people are critical, as they can be, think of them as trying to help, not diminish, you. I could have saved myself a lot of wasted time if I’d managed to do that. When a high school teacher wrote on my paper, “Janet, is this your own work?” and that college prof condescended to me with her smiling “an image is not a poem,” I’d be a lot farther along today if I’d taken the one as a compliment and the other as help. My belief wavered. We’re capable of believing anything—why not believe in our voices?

What’s great about writing in your part of Nova Scotia?

The great thing about writing in my part of Nova Scotia is the community I mentioned in question #3. There is such warmth in the folks of the South Shore. On Saturday, I was invited to be an “Author for Indies” in a lovely new bookstore, LaHave River Books. The store was humming. So many people, including many other writers, who’d come out to be present, to “show up,” to share in the celebration. I’m sure the day was the same for another independent bookstore, Lexicon Books, in Lunenburg. There’s Lunenburg Bound, too, almost next to Lexicon. Imagine! In an era when pundits say books are a thing of the past, we have that many independent bookstores, all within a half hour or less of where I live, all offering frequent author readings, all being supportive and encouraging. They wouldn’t be there if there were no book buyers in the area!

What’s the last great book you read?

The last great book I read was First Snow, Last Light, by Wayne Johnston. I closed the covers on it just day before yesterday. The last great book I read, immediately before that, was Acts and Omissions by Catherine Fox. In other words, I tend to think any book I enjoy fully is great. It’s how I feel about movies, and plays, and TV shows. I think of all the people who contributed to share that book or that show. I think how hard they worked, how hard they must have believed. I throw myself into their world, and don’t come out until it’s over. I always wish I could say “thank you” in person to the writer, the editor, the publisher, the government grant giver. I’m talking about well-written books, where the reader doesn’t have to think about the writing itself (other than to enjoy it), but only what is written. Readers know pretty quickly if the book they’re reading is their kind. I knew a person who said he gave a book 50 pages. In other words, if he wasn’t hooked by page 50, he closed the covers. It’s not a bad system. So much of what we respond to is taste. Who decides what is “great,” after all? The “canon” is almost 100% male. I rest my case.

What’s the last great movie you saw?

Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool was the last great film I saw. Yes, same story as for books—it was the last film I saw. But truly, it was what even iconoclastic critics might call great. Written by Matt Greenhalgh, after Peter Turner’s memoir; directed by Paul McGuigan; starring Annette Bening, who played Gloria Grahame: every single contributor shone. I was provoked, moved, disturbed, delighted. My aesthetic senses were thrilled. My intelligence was set alight and fanned. What more do we ask of art?

What are you working on right now?

Zoe Lucas of Sable Island fame and I are writing a sequel to my mother’s novel for young people, Pit Pony. Zoe wants to get Willie, a boy, and Sandy, a horse, to Sable Island. I’m writing the mainland parts, and she’ll do the Sable Island parts, and then we’ll try to make it sound like all one voice. Likely I’ll do the rewrite. My mother (the same Joyce Barkhouse, CM, ONS, as in the answer to the first question) gave us permission years ago, but we’ve just gotten to it. It takes place in the early 1900s in Nova Scotia so I’m having to do a lot of research about daily life then. It’s fun, though a different kind of fun than writing poems.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you be?

I’ve already had quite a few different roles. Chronologically, I’ve been a camp counselor, sales person, theatre student, parent, academic, professional actor, production assistant, pioneer, library technician, crafts person, shop owner, teacher, amateur theatre director—not to mention all the roles I had in the plays I acted in. That’s what can happen if you’re gifted with a long life, I guess. If I weren’t a writer, I’d be naturalist or a naturopath. I’ve always loved our Earth, identifying edible plants and fungi, naming wildflowers and wild shrubs. Perhaps I could turn that passion into work. Or could if I still had the memory of a young person. Since I don’t, I imagine I’ll continue to write, exploring Earth and its people’s roles and behaviours in poems and prose.

Author spotlight: Janet Barkhouse Read More »